Report By David Obi

John Odigie-Oyegun has discovered repentance—late, public, and televised.

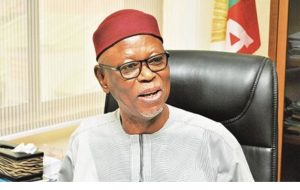

In a country where political architects usually deny the building collapsed, Nigeria’s former ruling-party midwife has done the unthinkable: he apologized. Appearing on Arise News, the founding National Chairman of the All Progressives Congress (APC) looked straight into the national mirror and said what many Nigerians have been screaming into generators for a decade: something went terribly wrong.

“I owe Nigerians an apology,” Oyegun said, effectively issuing a political confession of sins for the party that swept to power in 2015 on a tidal wave of hope, hashtags, and unrealistic expectations. The APC, he admitted, derailed “almost immediately.” Which in Nigerian political time translates to: before the champagne went flat.

Back then, Oyegun recalled, the air was thick with optimism. Democracy had finally been upgraded. Corruption would flee. Governance would arrive. Instead, Nigerians got what he now politely calls disappointment—and what citizens more bluntly call survival mode.

Now 86, Oyegun says he is not defecting; he is atoning.

His new political home, the African Democratic Congress (ADC), is not a party, he insists, but a “rescue mission”—the political equivalent of calling an ambulance long after the accident, but before the burial. As chairman of a 50-member committee drafting the ADC manifesto, Oyegun says Nigeria’s problems are no longer ideological. They are existential. This is not politics as usual; this is triage.

Looking back at the APC years, Oyegun was unsparing. He says he warned President Muhammadu Buhari early on that things were falling apart. Buhari, according to him, replied that he wanted to be a “true civilian president,” not the rigid general of old. Oyegun interpreted this as a refusal to discipline underperformers—an administration allergic to consequences, armed with good intentions and poor execution.

Then came the Tinubu era, which Oyegun describes with a word Nigerians felt in their wallets: traumatic.

Yes, fuel subsidy removal was inevitable, he said. But inevitability without preparation is just policy-induced shock. In his telling, Nigerians did not transition from hardship to reform—they plunged from hunger to starvation, with no safety nets, buffers, or apologies included.

Looking ahead to 2027, Oyegun paints a stark battlefield: on one side, the “oppressors,” conveniently united under one umbrella; on the other, the Nigerian people—tired, poorer, and dangerously patient. The mass migration of governors and political heavyweights into the APC, he warned, has turned the next election into less of a contest and more of a referendum.

But even in repentance, Oyegun is practical. He cautioned opposition figures—Peter Obi, Atiku Abubakar, and friends—that ego could yet ruin what he calls “Nigeria’s last card.” Unity, numbers, and cold electoral math must trump ambition. Romance, he suggests, has already failed this country once.

At 86, Oyegun says he is done chasing power. What he wants now is legacy—preferably one that includes an apology footnote rather than a political obituary.

“My prayer,” he said, “is to see Nigeria out of the woods before I leave this world.”

It is a striking moment: a founding father returning to the ruins, asking forgiveness, and offering a new blueprint. Whether Nigerians see this as redemption, revisionism, or too little too late may decide not just Oyegun’s legacy—but the story Nigeria tells itself in 2027.